Roger Pepin has spent years watching the herring run up the Acushnet River each spring. He grew up along the river, and he remembers the schools of herring that used to swim upstream by the thousands – so many fish that he couldn’t see the bottom of the river.

The Acushnet River is one of countless places around Buzzards Bay where healthy streams and wetlands have been lost. As a result, the river’s once-vibrant fish populations have dwindled. The Coalition is working to restore damaged streams and wetlands in places like the Acushnet River, the Weweantic River, and the Mattapoisett River to protect clean water and improve the health of the Bay ecosystem so fish, wildlife, and people can thrive.

Why are streams and wetlands important to Buzzards Bay?

Freshwater streams and rivers create a vast network of waterways that connect our communities to Buzzards Bay.

The long-term health of Buzzards Bay depends on healthy streams and wetlands. These natural areas are essential parts of the Bay ecosystem. Streams and wetlands provide shelter for fish and wildlife, and they help protect clean water in the harbors, coves, and rivers where people love to swim, fish, and dig for clams.

Streams

More than 700 miles of small streams flow through the Buzzards Bay watershed to our tidal rivers, harbors, and the Bay. These streams create a vast network of waterways that connect our communities to the Bay.

Freshwater streams provide important habitat for fish that migrate from Buzzards Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. Species like river herring, white perch, and sea-run brook trout swim upstream each spring to spawn. And young American eels journey upstream from the ocean to spend their lives in freshwater streams and ponds.

These small fish might seem unimportant. But if you like fishing for stripers and bluefish in Buzzards Bay, then you should care about river herring. They’re a major food source for sportfish and water birds, and form an important link in the Bay food web.

Wetlands

Salt marshes, such as this one at Eel Pond in Mattapoisett, are a type of wetland that protects clean water and provides habitat for wildlife.

Wetlands are low-lying places like salt marshes and wooded swamps that are naturally wet. These rich habitats are powerful pollution filters that can absorb as much as 90% of the nitrogen pollution flowing across the land from nearby development. They also provide habitat for a diverse array of wildlife, from fish and crabs to birds, mammals, and reptiles.

With climate change, wetlands are more important than ever. The salt marshes that fringe our coastline and filter out pollution also protect our homes, beaches, and businesses from rising waters. As sea levels increase, restoring wetlands builds the Bay’s resilience against climate change.

Why do we need to restore streams and wetlands?

Throughout the Buzzards Bay region, thousands of acres of natural streams and wetlands have been filled, blocked, and drained. This damage to our streams and wetlands from poorly planned development, dams and road culverts, and invasive species harms the health of the entire Bay ecosystem.

Poorly planned development

River herring and other migratory fish have a hard time swimming past dams, like this one at Horseshoe Mill on the Weweantic River.

For a long time, people considered wetlands to be unimportant. Thousands of acres of swamps and salt marshes around Buzzards Bay were drained, filled, and torn away to make room for new homes and businesses.

As a result, 40% of the Bay’s original wetlands have been lost. And despite layers of laws that are supposed to protect wetlands, the Bay continues to lose roughly 20 acres of wetlands to development every year. Poorly planned development takes away our precious remaining wetlands. In waterways where pavement and buildings have taken away wetlands, we can see the effects on the water’s health.

Poorly planned development has also stripped away forested buffers from the banks of streams and rivers. Trees and plants that grow along streams create a natural buffer that captures pollution and prevents erosion. They also provide shade over streams, which is vital for species like sea-run brook trout that can only spawn in clear, cold water.

Nearly one-third of the Buzzards Bay watershed’s stream buffers have been lost to development. Without healthy forested buffers to protect our streams, polluted stormwater runoff from roads and parking lots rushes into nearby streams and destroys spawning habitat for fish.

Dams, culverts, and other blockages

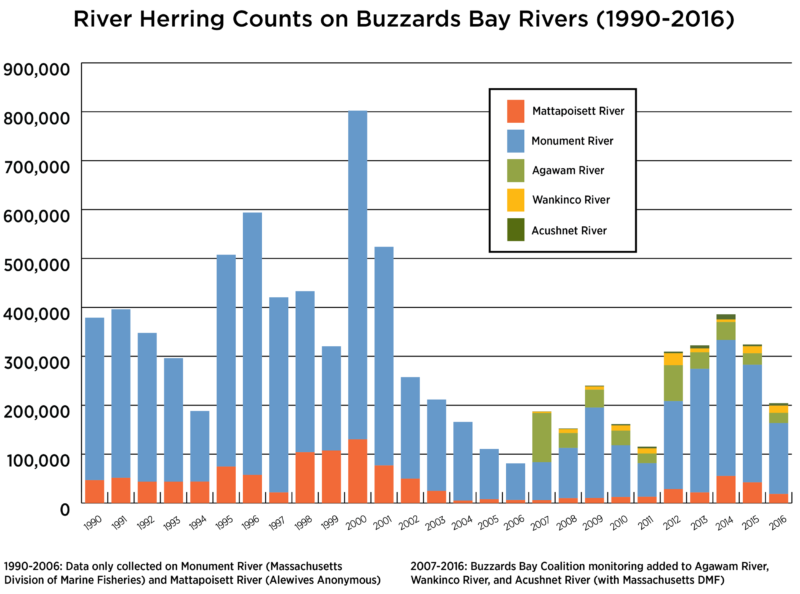

Although river herring populations have increased slightly over the past decade, they remain dangerously low. (Download full data from 1990-2017)

Dams, road culverts, and other obstructions block nearly all of Buzzards Bay’s major rivers and small streams. These man-made structures alter the natural flow of our streams and rivers.

People started building dams on rivers in the 1700s to power mills. But after the mills disappeared, the dams remained. And as transportation expanded throughout the region, culverts were installed so water could pass under roads built across streams. In other areas, streambanks have been channeled through cranberry bogs or hardened with concrete, creating even more problems.

In short – many of the Bay’s streams and rivers are broken. As a result, the Bay’s migratory fish are suffering, which has negative effects throughout the Bay ecosystem.

River herring and other migratory fish have a hard time swimming past tall dams, dark culverts, and narrow channels to reach their freshwater spawning grounds. Fish ladders have been installed at many dams, but they’re rarely successful. If river herring can’t reach their spawning areas, they’re much less likely to reproduce.

Dams and blockages are one of the biggest problems facing river herring, eels, and other migratory fish. Only a tiny fraction of the historic populations of herring still make the journey upstream each spring. Some species that used to be abundant here, such as shad, sturgeon, and Atlantic salmon, are entirely gone.

Invasive species

Buzzards Bay’s tidal wetlands have been invaded by a nonnative plant called Phragmites, also known as the common reed. You’ve probably seen these tall, tufted stalks growing along rivers, beaches, and roadsides. Phragmites is familiar – but unwelcome. This invasive plant isn’t native to our region, and it takes over the wetlands where it grows.

Once Phragmites becomes established, it’s difficult to completely remove it because it spreads so easily. But it can be done. At three salt ponds in Dartmouth and Falmouth, the Coalition has completed a model project to wipe out Phragmites and restore wildlife habitat at these ponds.

Where is the Coalition restoring streams and wetlands?

At The Sawmill on the Acushnet River, the Coalition worked with NOAA to improve passage for river herring migrating upstream to spawn.

The Coalition works throughout the Buzzards Bay watershed to restore damaged streams and wetlands. It’s a critical part of our work to conserve the land that surrounds the Bay.

Our restoration work today is centered around the Acushnet River, the Mattapoisett River, and the Weweantic River. In these three places, a significant amount of wetlands have been lost and streams have been altered. As a result, clean water has suffered and fish populations continue to dwindle.

But our restoration projects in Acushnet, Wareham, and Mattapoisett are just the beginning. We’re also working on a plan to prioritize other places around Buzzards Bay where streams and wetlands need to be restored.

By rebuilding these natural pollution filters and restoring fish passage, we can bring back the Bay’s healthy streams and wetlands for all.

Acushnet River Reserve

At the edge of New Bedford’s urban North End sits The Sawmill, a 19-acre former industrial lumber yard on the Acushnet River. The Coalition recently transformed The Sawmill into a public park that protects the river’s health and offers local residents a beautiful place to enjoy the outdoors.

This part of the Acushnet River has experienced centuries of industrial use. For nearly 300 years, a dam blocked migrating fish from reaching their freshwater spawning grounds. Pavement and buildings used to cover the ground, and tall granite blocks walled off the river’s banks.

Now, all of that has changed.

Working with hundreds of local residents, the Coalition restored The Sawmill to bring back the natural habitats that once thrived along this stretch of the Acushnet River. A restored red maple swamp and native stream buffers filter out pollution and protect clean water in the river.

In 2007, the Coalition worked with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to lower the dam and build a nature-like fishway on the river. This innovative fishway uses carefully placed boulders that mimic the river’s natural form and allow river herring to migrate upstream.

This project has already achieved positive results: Since 2007, we’ve recorded a significant increase in herring in the Acushnet River. The Acushnet River is now the only major river on Buzzards Bay that’s unbroken – fish can swim all the way from the Bay to the river’s headwaters at the New Bedford Reservoir.

Weweantic River Reserve

Restoring the Weweantic River at Horseshoe Mill will improve spawning habitat for species like rainbow smelt, a small fish that lays its eggs in the river here.

With The Sawmill as our model, the Coalition is now beginning a process to restore the Weweantic River at Horseshoe Mill in Wareham. Like The Sawmill, Horseshoe Mill is a former industrial site that’s located on the river at the head of tide. A crumbling dam sits at this special spot, blocking fish from migrating upstream to spawn.

There’s a lot at stake for fish in the Weweantic, Buzzards Bay’s largest freshwater river. Even with this blockage, the Weweantic River is still home to the Bay’s most diverse community of migratory fish – a mere fragment of the type of fish populations that used to live in all of the Bay’s rivers.

Restoring the river at Horseshoe Mill is an amazing opportunity to bring back fish and wildlife populations on the Bay. This project will improve spawning habitat for species like rainbow smelt and open up the river so eels, river herring, and other migratory fish can swim farther upstream.

Mattapoisett River Reserve

In the heart of the Mattapoisett River Valley lies the Mattapoisett River Reserve, a growing 400-acre swath of forests, streams, and freshwater wetlands. These natural areas protect an underground drinking water aquifer that thousands of residents in Fairhaven, Mattapoisett, Rochester, and Marion use every day.

The centerpiece of the Mattapoisett River Reserve is Tripps Mill Brook, a stream that links Tinkham Pond with the Mattapoisett River. Roughly 50,000 river herring migrate up the Mattapoisett River each spring to spawn – the largest herring population on Buzzards Bay.

Because of the Mattapoisett River Reserve’s importance to fish, wildlife, and people, the Coalition has forever protected this area from development. Working in partnership with the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, we will restore native wetlands at The Bogs, where 55 acres of retired cranberry bogs now sit, and improve passage for fish at Tripps Mill.