What 25 years of river herring data tell us about restoring these ‘foundation’ fish in Buzzards Bay

Four centuries ago, Buzzards Bay’s local rivers ran silver with herring each spring. These small fish — which are an important source of food for striped bass and other large sportfish — migrate from the ocean every year to spawn in freshwater streams and ponds. But today, only a tiny fraction of the historic populations of river herring still make the annual journey upstream. Data collected over the past 25 years offer a snapshot of the decline of these “foundation” fish and hint at possible solutions to bring their populations back to health in Buzzards Bay and beyond.

Why have river herring populations declined?

Fish ladders have been installed at many dams, but they aren’t always successful. If river herring can’t swim upstream to reach their spawning areas, they’re much less likely to reproduce.

There are a number of factors that have led to the decline of river herring populations over the past century, including pollution and overfishing.

Dams, road culverts, and other blockages are one of the biggest problems facing migratory fish. River herring and other migratory fish have a hard time swimming past tall dams and narrow road culverts to reach their freshwater spawning grounds. If river herring can’t reach their spawning areas, they’re much less likely to reproduce.

There’s another important cause of the decline of river herring – this one located far away from Buzzards Bay, out at sea. Fishing vessels that trawl for commercially valuable species like mackerel and Atlantic herring can accidentally catch river herring in their nets. This is called “bycatch.” Fisheries managers believe that some of the past decade’s declines can be linked to river herring being caught inadvertently as bycatch.

At first glance, river herring might not seem very important. But if you like fishing for striped bass and bluefish in Buzzards Bay, then you should care about river herring. They form an important link in the Bay food web, providing a major food source for popular sportfish as well as fish-eating water birds.

Where are river herring tracked in Buzzards Bay?

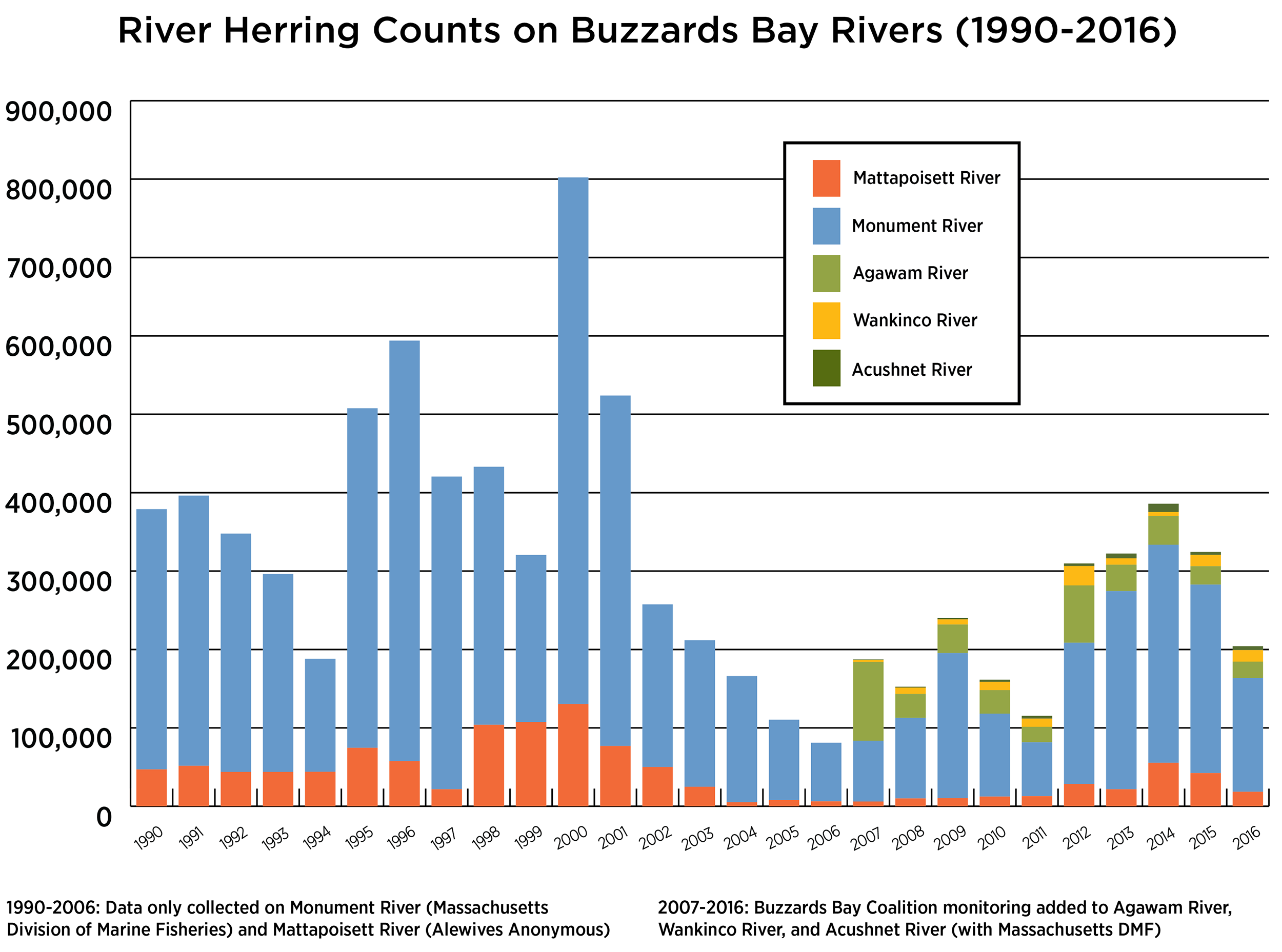

Although river herring populations have increased slightly over the past decade, they remain dangerously low.

Since 2007, the Coalition has monitored river herring populations in the Acushnet River, the Agawam River, and the Wankinco River. Every spring, the Coalition sets up counters on each of these rivers to track how many herring are swimming upstream. Recently, we’ve also added counters to the Sippican River and Cedar Lake/Rands Harbor to get a more comprehensive view of river herring populations across Buzzards Bay.

In addition to the Coalition’s counts, the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries (DMF) tracks herring migrating up the Monument River (Cape Cod Canal herring run) and Alewives Anonymous tracks herring in the Mattapoisett River.

Because it has the longest dataset, the Mattapoisett River serves as our local benchmark for tracking river herring populations. In 1921, when monitoring on the Mattapoisett River began, 1.85 million river herring were counted. Last year, just 18,540 fish were counted – only 1% of that historic high from nearly 100 years ago.

Although river herring populations have increased slightly over the past decade, they remain dangerously low. In the 2015 State of Buzzards Bay report, the score for river herring was only 2 out of 100.

The problem isn’t limited to Buzzards Bay. Up and down the East Coast, rivers have recorded historic low river herring populations in recent years. Because there are so many factors that influence river herring populations, it’s hard to pinpoint a single cause of these declines in any given year.

What is being done to protect and restore river herring?

At The Sawmill on the Acushnet River, the Coalition worked with NOAA to improve passage for river herring migrating upstream to spawn.

On a local scale, projects to eliminate blockages and reopen rivers to fish passage are making an enormous difference for river herring and other migratory fish. Across the Buzzards Bay region, the Coalition is working to restore damaged streams where river herring once flourished.

The positive effects of river restoration are clear on the Acushnet River, where river herring populations have increased tenfold since a dam at The Sawmill was lowered in 2007. That year, the Coalition worked with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to build a nature-like fishway that allows river herring to migrate upstream. The Acushnet River is now the only major river on Buzzards Bay that’s unbroken: fish can swim all the way from the Bay to the river’s headwaters at the old New Bedford Reservoir.

With The Sawmill as our model, the Coalition is now beginning a process to restore fish passage at Horseshoe Mill on the Weweantic River, Buzzards Bay’s largest freshwater river. A crumbling dam currently sits here, blocking fish from migrating upstream to spawn. By restoring the river at Horseshoe Mill, we can open up the river again for herring and other migratory fish.

Both here and across the East Coast, there’s still a lot more work to be done to protect river herring for generations to come. But with increased restoration on our local rivers and proper fishery regulations, these important fish can return to health.