Where to go beachcombing on Buzzards Bay — and 14 objects to look for

Beachcombing is a fun activity for kids of all ages throughout the year.

Every day, waves, wind, and the ceaseless cycle of the tides touch more than 200 miles of shoreline around Buzzards Bay. As the water comes and goes, it leaves behind an incredible variety of objects from the sea. For beachcombers, the Bay’s combination of exposed shores and protected coves offer a banquet to explore.

The best time to comb the beach is usually after a stormy or windy day, when large waves lift heavier items and wash up objects from deeper waters. You’ll find some of the best treasures in the “wrack line”: the thick ribbon of seaweed, shells, and debris that forms on beaches at the high tide line.

Although beachcombing is a four-season activity, winter can actually be the best time to take a beach walk: winter storms often bring some of the best finds ashore, and fewer crowds mean you have a better chance of finding a treasure.

Here are 14 of the most common shells and objects you might find when you go beachcombing – and a list of Buzzards Bay beaches to get you started on your adventure.

What shells and objects can I find on Buzzards Bay’s beaches?

From clams to scallops to egg cases, Buzzards Bay’s beaches offer a treasure trove of fascinating objects to find. These 14 are just a few of the dozens of species you might discover between the wrack line and the waves. For more, pick up a good beachcombing field guide as a reference.

There’s another thing you’ll probably find when you go beachcombing: trash, particularly plastic. If you want to help keep the Bay’s beaches clean, bring a disposable bag with you on your walk to pick up any trash you come across.

Slipper shells form stacks of several animals high.

1. Slipper shells

Slipper shells may be the most common shell you’ll find on local beaches. They wash up in thick pink, purple and cream layers in many wrack lines. There’s little question where these curved, flat-bottomed shells get their name: flip one over and you’ll see a little shelf that closely resembles the opening to a slip-on shoe.

These pretty pastel shells are also home to snails with a very interesting life. Slipper shells form high stacks atop one another on rocks or other shells. The bottom of the stack is always a female, and the shells above all males. If there are too many males in a stack, or the bottom female is lost, the slipper snail has a quick fix: the bottom-most male transforms from male to female, preserving the group’s ability to continue reproducing.

2. Quahogs

Digging for live quahogs is a fun activity for all ages.

The name quahog comes from the clam’s Native American name, “poquauhock.” These edible clams are one of our most popular shellfish. Whether you find them along the shore or gather them up after eating their delicious contents, quahog shells are also lovely to collect, with swirls of dark purple and blue on their interiors.

Though no two quahog shells is alike, there is one particularly distinctive group you may find around Buzzards Bay. Quahogs seeded by towns and aquaculture farmers for harvest are usually of the notata strain, a natural but otherwise rare variety. These clams have distinctive streaks and zig-zags of color across their exterior, making them a particularly exciting find for the beachcomber.

3. Oysters

Oysters grow on top of each other and form dense reefs. Many species, such as crabs and small fish, depend on oyster reefs as a place to hide from predators.

Though another popular edible shellfish, the American oyster is a bit rarer around Buzzards Bay than it once was, due to over-harvesting and nitrogen pollution. However, efforts by local towns to seed harbors with oysters are starting to bear (delicious) fruit, and there are a growing number of places around Buzzards Bay where you can find these strange, knobby shellfish.

When alive, oysters clump together in large “reefs,” usually on rocks and other hard surfaces. When their shells wash ashore, they’re distinctive for the smooth, silvery layers of material known as “mother of pearl” on their interior side, which is particularly beautiful when used in jewelry.

4. Mussels

Blue mussels grow in groups on hard surfaces, like rocks, piers and docks.

There are two types of mussel shells you might find around Buzzards Bay. Blue mussels have a smoother shell in dark blue, purple and black, banded with silvery stripes, and grow in large groups on hard surfaces in coastal waters. Ribbed mussels are a muted brown or green, with textured lines on their shells, and live partially buried in sand or mud. Their favorite place to live is at the base of marsh grasses, where they happily filter material from the water.

Both of these mussels are very common, but because their shells break easily, it’s a treat to find one whole and well-worn by the waves. The interior of a mussel, which fades from bright pearl at the tip to blue and purple around the edge, can be particularly beautiful to use in jewelry and decorations.

Bay scallops are smaller and more colorful than sea scallops. (Image: Plant Image Library)

5. Scallops

Much like oysters, the shallow-water bay scallops that were previously common around Buzzards Bay have all but disappeared. This is largely due to nitrogen pollution, which clouds the water and makes it hard for eelgrass — bay scallops’ favorite habitat — to grow. While it is difficult to harvest bay scallops commercially or recreationally, there are places around Buzzards Bay where these blue-eyed beauties still swim.

Bay scallops’ ridged, fan-shaped shells come in many colors, often with bands of different pigments running across their ridges. If you’re searching outer Buzzards Bay beaches, you may also come across the shell of a sea scallop, the bay scallop’s deep-water cousin. These shells are larger and flatter, often a more uniform reddish-brown in color, and have little or no distinctive ridges.

6. Cockles

This worn white cockle is likely a blood cockle with its outer coating stripped off by the waves.

These strong, ridged shells look something like a cross between a quahog and a scallop, and form a pretty heart shape when closed. On Buzzards Bay shorelines you may find the common cockle, a white or cream shell with bands of tan and brown, or the “blood cockle,” a white shell coated with hairy, greenish-black material. Also known as the blood ark or blood clam, these clams get their vivid name for the bright red liquid and muscle tissue you’ll find if you open one. After tumbling in the surf for a long time, blood cockle shells often lose their layer of dark “hair,” leaving their shells pure white.

The blood cockle is a very popular food in Asia, where it is eaten both raw and cooked. Its gory appearance has long been rather off-putting to New England diners, but some chefs are trying to introduce this abundant, but underutilized, clam to local palates.

7. Moon snails

Moon snails have soft bodies that are 2-3 times larger than their shells.

The shell of the northern moon snail is a perennial favorite find for its spiral shape and stunning colors: pink, cream, and orange, swirled with dark blue and purple. The carnivorous snails that live within can live as long as 15 years, and grow shells as large as 7 inches long in that time. What’s more, a snail’s body can inflate up to four times the size of its shell— making them a real treat for kids to examine. You’ll find these snails primarily in calm, sandy bays and beaches. In the summer, you may also find “sand collars,” flexible semi-circular masses of compressed sand, which hold thousands of moon snail eggs.

Moon snails are also the reason you may find other shells on the beach with perfectly round holes in them, often near the hinge— perfectly placed to make into jewelry! Moon snails use a long tongue-like structure called a radula, along with a potent acid, to drill these holes while hunting other shellfish.

8. Periwinkles

You’ll find invasive common periwinkles gathered by the hundreds on Buzzards Bay shores. (Image: Alexey Sergeev)

Periwinkles are a common sight in tide pools, grazing on algae and seaweed, but you’ll also see them carving lines in sandy beaches, gathering on piers and docks, and clinging to rocks beneath crashing waves. Around Buzzards Bay you’ll find three types: the rough periwinkle (blueberry-sized, with a cone-shaped shell), the smooth periwinkle (slightly larger than the rough, with a round and often brightly colored shell) or the common periwinkle (as large as a grape, with a dark brown shell). Unfortunately, the common periwinkle is invasive, and can wreak havoc on shorelines by devouring every marine plant in sight.

You may have grown up hearing that you can get periwinkles to emerge from their shells by humming to them. Research suggests that there’s little proof that this persuades periwinkles to peek out — however, it remains a great activity to keep kids busy at the beach.

This tiny periwinkle or dog whelk shell, found on Onset Beach, is now home for a hermit crab.

9. Dog Whelks

Dog whelks closely resemble smooth periwinkles, but they have a bumpier shell surface and longer, more pointed spire at the end of their shell. Dog whelk shells can also feature garish striped patterns in brown, chestnut, black, and pure white. These small snails prefer to stay beneath the tide line on rocky shores, where they can feast on mussels, barnacles, and periwinkles — making these little predators a good check on the invasive common periwinkle where they overlap.

10. Mermaids’ toenails

Shiny mermaid’s toenails are also called “jingle shells,” as they make lovely windchimes. (Image: Alexey Sergeev)

Sadly, “mermaids’ toenails” do not come from mythical fish people. Rather, these distinctive shells belong to the Anomia simplex clam. Their thin, almost transparent shells come in orange, yellow, pink, gray and white, and have an iridescent mother-of-pearl shine. These shells are also known as jingle shells, as they can be strung together to make wind chimes.

Mermaids’ toenails are often dispersed by commercial aquaculture, as they form a good surface upon which young oyster spat settles. As such, these shells can often be found in the same places where oysters are seeded by towns or in shellfish farming. These shells can also be found on most shallow water beaches, though we recommend looking for them on calmer shores, where they’re less likely to be broken up by waves.

11. Knobbed & Channeled Whelks

This channeled whelk, found on West Island, has a prominent operculum- the dark-colored “door” it uses to seal its shell when it gets too dry.

New England’s large whelks are often victims of mistaken identity: they’re commonly referred to as “conch,” which are actually their warm-water cousins. The whelks in our waters belong to two species: the channeled whelk, which has a flat ridge running around its spire; and the knobbed whelk, which instead has rounded spikes around its spire. A whole whelk is a beachcomber’s gem, coming in magnificent colors marbled and striped like watercolor paint. They’re also particular favorite for kids to hold up to their ears and listen to the echo of the ocean.

You might also be lucky enough to find a live whelk, especially if you’re out digging for quahogs. Whelks, too, like to eat these delicious clams, and can be found buried in the sand in pursuit of them. Live whelks are quite active; if you find one alive, take a few minutes to appreciate its muscular foot and the fingernail-like “operculum” it uses to seal off its shell before returning it home

12. Whelk egg casings

Break open a whelk egg casing to find thousands of tiny shells.

You’ve probably walked past whelk egg casings — spiral strings of light-colored, papery packets — dozens of times without realizing what you were looking at. Break one of these packets open and you’ll find an amazing sight: hundreds and hundreds of tiny baby whelks, their shells already perfectly formed, despite being around the size of a sesame seed.

Whelks lay these egg casings in the winter, and will bury one end in sand or mud to prevent them from washing ashore. As such, they’re most abundant in the winter and spring, and a common sight on the beach after storms.

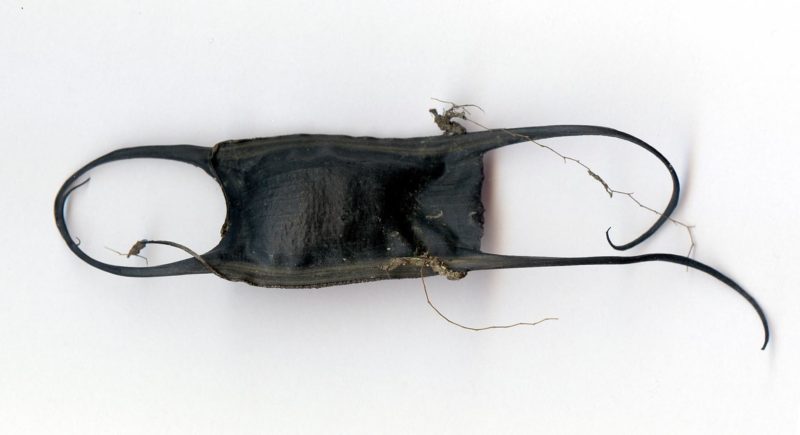

13. Mermaid’s Purse

Skate cases found on the beach are usually from hatched baby skates, but after a storm you may find one with a live skate still inside! Image: Invertzoo)

Also known as a “devil’s purse” due to the curling horns at their corners, these dark capsules are the egg cases of skates. (Those horns secure the egg case to plants and rocks while a baby skate grows inside.) Around Buzzards Bay, mermaid’s purses most likely belong to one of two skate species: the little skate or the winter skate. The little skate’s egg cases are dark brown to nearly black with one set of short horns and one set of long horns, while the winter skate’s cases are greenish brown with four very long, skinny horns.

Mermaid’s purses can be found on the beach any time of year. They’re usually empty, but occasionally you may find a living egg cases that has washed up during storms. Living egg cases are heavier and leathery; you can check by holding the case up to the sun or a flashlight and looking for something wriggling inside!

14. Horseshoe Crab Molts

They may look like dead crabs, but these empty shells are actually the old skins that horseshoe crabs shed as they grow.

You’ve probably spotted the brown, helmet-like shapes of horseshoe crabs scattered on the sand of local beaches in late summer and early fall. Often, these aren’t dead crabs – they’re old shells that horseshoe crabs molt and discard as they grow. If you happen to find a fresh molt that hasn’t yet dried and hardened, you should be able to peel open the front section, below the eyes, and look into the space where the crab used to live.

Horseshoe crab molts can make great decorations, especially since they look so life-like. Just be sure to dry the molt thoroughly in the sun to ensure that this shell doesn’t bring any odd smells from the beach into your home!

Where can I go beachcombing on Buzzards Bay?

Nearly all of Buzzards Bay’s beaches offer great beachcombing adventures. Here are a few ideas to get you started!

Easy beachcombing spots for families

Little Harbor Beach in Wareham offers a sheltered shoreline that’s easy for kids to explore.

Beachcoming is a fantastic activity for kids and families. If you want to go to a beach that offers great beachcombing in a small area, check out these places:

- Goosewing Beach Preserve (Little Compton)

- Gooseberry Island (Westport)

- Apponagansett Park (Dartmouth)

- Fort Taber Park (New Bedford)

- West Island Town Beach (Fairhaven)

- Fort Phoenix State Reservation (New Bedford)

- Shining Tides Beach (Mattapoisett)

- Planting Island Beach (Marion)

- Shell Point Beach (Wareham)

- Squeteague Harbor Beach (Bourne)

- Wood Neck Beach (Falmouth)

Beaches with a walk

The rocky, wave-exposed shores of Gooseberry Island can hold interesting treasures tossed up by outer Buzzards Bay.

Long walks on the beach aren’t just for romance – they offer the chance to linger and look for more unique objects along the shore. These beaches are excellent spots to get in a walk with your beachcombing adventure.

- Horseneck Beach State Reservation (Westport)

- Round Hill Town Beach (Dartmouth)

- Winsegansett Marshes (Fairhaven)

- West Island State Reservation (Fairhaven)

- Nasketucket Bay State Reservation (Mattapoisett)

- Munn Preserve (Mattapoisett)

- Brainard Marsh (Marion)

- Lyman Reserve (Wareham/Plymouth/Bourne)

- Lawrence Island (Bourne)

More remote beachcombing spots

Want a true beachcombing adventure? These beaches are all located on islands, which means you’ll need a watercraft of some kind to reach them. But when you get there, you’re bound to discover some amazing objects on these shores!

- Wickets Island (Wareham)

- Bassetts Island (Bourne)

- Church’s Beach (Gosnold)

- Barges Beach (Gosnold)

- Menemsha Hills (Martha’s Vineyard)