In Tampa Bay, collaboration leads to successful seagrass restoration

When you think about bold, successful initiatives to protect the environment, Florida may not be the first place that comes to mind. Rapid population growth, poorly planned development, and the effects of a warming climate have left the Sunshine State vulnerable to pollution, particularly along the coast.

But in Tampa Bay, things are looking up. Earlier this year, officials with the Tampa Bay Estuary Program (TBEP) announced they had met an aggressive goal to restore the bay’s underwater seagrasses to levels not seen since 1950. How they did it is a story of collaboration in the face of environmental degradation, showing that when people work together over time, our waters can thrive.

In estuaries like Tampa Bay and Buzzards Bay, seagrasses are a key indicator of the water’s health. When there are lots of seagrasses, that means the water is clear and full of life. But a type of pollution called nitrogen pollution — which comes from people like you and me — is taking a toll on seagrasses in coastal waters around the country and the world.

It’s difficult to find large-scale success stories in the effort to clean up nitrogen pollution. On the Chesapeake Bay, governments and businesses have spent billions with few positive results for the water’s overall health. And in Long Island, Narragansett Bay, and countless other waterways, nitrogen pollution from wastewater, agriculture, and sprawling development seems hard to overcome.

The triumphant return of seagrasses to Tampa Bay proves that it’s possible to protect clean water, even in places with millions of people and countless pollution threats.

Why did seagrasses die off in Tampa Bay?

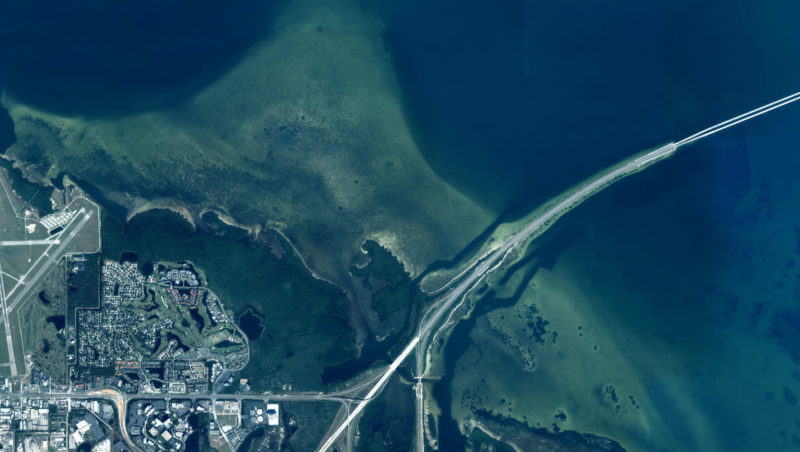

Algae blooms like this one in Tampa Bay cloud the water, which blocks sunlight from reaching seagrasses at the bottom. (Image: Dorian Aerial and Architectural Photographics)

Starting in the 1950s, seagrasses in Tampa Bay began a steady decline that lingered through the 1990s. The culprit for this die off? Nitrogen pollution.

Nitrogen pollution is the biggest threat facing coastal waterways like Tampa Bay and Buzzards Bay. The major source of nitrogen pollution is people — largely wastewater, because older sewage treatment plants and standard septic systems don’t treat for nitrogen. In Tampa Bay, nitrogen pollution began to build up in the bay from poorly treated sewage, industrial discharges, untreated stormwater runoff, and unrestricted dredging and filling.

More than 2 million people live around Tampa Bay — double the population that lived there just 20 years ago. It’s a relatively shallow body of water, averaging just 12 feet deep. With so many people living in the region and contributing pollution, the bay began to suffer.

Nitrogen pollution is harmful because it acts like fertilizer, fueling the growth of algae in the water. When our coastal waters become cloudy and murky with algae, seagrasses can’t grow because not enough sunlight can reach them. The amount of algae in the water is one of the most important factors affecting the growth of seagrasses.

Tampa Bay’s pollution problems got so bad that when 60 Minutes ran a segment about nutrient pollution in the U.S. in the late 1970s, Tampa Bay was its poster child. By 1982, the bay had lost half of its seagrasses and natural marsh shoreline. “Fish kills” — massive die-offs of fish due to lack of oxygen in the water — were common. In some places, you couldn’t see more than 2 feet down in the water.

Today, a similar story is playing out here in parts of Buzzards Bay. Places like West Falmouth Harbor, the Westport Rivers, and Apponagansett Bay have less eelgrass than they ever have before. Here, residential septic systems are the biggest problem. But wastewater treatment plants, fertilizer, air pollution, and animal waste all play a role in Buzzards Bay’s dwindling health.

Why are seagrasses important to Tampa Bay and Buzzards Bay?

Eelgrass grows in the shallows in Woods Hole, providing habitat for fish, crabs, and bay scallops.

Seagrasses are vital to the health of every estuary, from Tampa Bay to Buzzards Bay. Young fish, crabs, and bay scallops seek shelter from larger predators among dense seagrass beds. Scientists in the Chesapeake Bay have found 30 times more juvenile blue crabs in underwater grasses than in areas with no grasses.

Additionally, seagrasses help improve the health of our coastal waters. They reduce erosion by anchoring bottom sediments with their roots and softening the force of waves along the shore. They also absorb nutrients and add oxygen to the water.

More underwater grasses is good news for fish, shellfish, and people who love the water. But the clean water is also a boon to local economies. According to the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council, one out of every five jobs in the region depends on a healthy bay. Including tourism, hospitality, and real estate, clean water in Tampa Bay translates to about $22 billion per year. That’s approximately 13% of the economy for all six counties around the bay.

In 1995, TBEP set a goal to restore 38,000 acres of seagrasses — the amount that existed in Tampa Bay in 1950, before the bay’s pollution problems became so serious. “It was an aggressive, but achievable goal over time,” said TBEP Executive Director Holly Greening, who runs this collaborative program to build partnerships to restore and protect Tampa Bay. “We didn’t know how long it would take.”

How did people work together to restore seagrasses in Tampa Bay?

Seagrasses are now flourishing in the shallow waters of Tampa Bay. (Image: Southwest Florida Water Management District)

Restoring Tampa Bay’s seagrasses has been the result of citizen action, government regulations on the biggest nitrogen pollution sources, and regional collaboration among local governments and industries.

The effort to reduce nitrogen pollution to Tampa Bay began all the way back in 1978. That’s when public outcry over the bay’s pollution woes grew so loud that the state of Florida took action to stop one of the biggest sources of nitrogen: sewage treatment plants.

The Tampa wastewater treatment plant was upgraded, and today is the world’s largest denitrification plant. In other nearby places, such as St. Petersburg, treated wastewater was reused for irrigation instead of being discharged directly to the bay.

Within a few short years, these improvements made a difference: By 1981, 90 percent of the nitrogen discharged from local wastewater treatment plants to the bay had been reduced. “That really kickstarted recovery in Tampa Bay,” said Greening. On top of these massive pollution reductions, Florida also enacted stormwater runoff regulations that boosted bay health even further.

With these new regulations, Tampa Bay had addressed its biggest sources of nitrogen. But as the area’s population continued to expand, new sources of pollution — roads, lawns, parking lots, and other hallmarks of development — were quickly taking their place.

To achieve the seagrass restoration goal, officials in Tampa Bay needed to reduce enough nitrogen pollution to clear up the algae that was blocking sunlight from reaching grasses at the bay’s bottom.

Through science and modeling, TBEP found the limit of nitrogen pollution that would still support healthy seagrass populations in Tampa Bay. This cap — called a TMDL, or Total Maximum Daily Load, under the federal Clean Water Act — became a nitrogen management goal that more than 45 local governments, utilities, and private companies are working together to achieve through the Tampa Bay Nitrogen Management Consortium.

“Partners have been vital to Tampa Bay’s recovery,” said Greening. “The public sector realized that these nitrogen management goals were unattainable without help.”

Through the Nitrogen Management Consortium, partners have completed over 500 projects to reduce nitrogen pollution to Tampa Bay. Included in the mix were wetlands restoration, regional stormwater runoff treatment, and shifts to cleaner natural gas to power utilities. Some counties banned the use and sale of residential lawn fertilizer in summer, when frequent rain storms sweep nutrients toward the bay.

In the beginning, the consortium’s initiatives were voluntary, with no requirements or allocations. But beginning in 2009, partners had to make firmer commitments to reduce nitrogen to meet federal and state regulatory goals for Tampa Bay’s health.

Working together, consortium partners developed and agreed to voluntary “caps” on nitrogen loads. Collectively, these allocations meet the overall nitrogen management goal that would allow seagrasses could thrive.

This collaboration worked — the caps were incorporated into state permits, and the nitrogen pollution limits set in the federal cleanup plan for Tampa Bay are being met.

“With so many different sources of nitrogen, it takes effort on many different parts not to break the caps that are now in effect,” said Greening. “There was recognition that we had to work together to reach this goal that we’d all agreed to.”

The results of the consortium’s efforts are impressive: Nitrogen pollution to Tampa Bay has decreased by half compared to 1976. Overall, the region has seen an 80 percent reduction in total nitrogen per capita — even as the population drew grammatically with a million more residents.

And this year — 20 years after the seagrass restoration goal was set — Tampa Bay surpassed the amount of underwater grasses recorded in 1950.

“I had thought maybe we might meet the goal in 2030,” said Greening. But as seagrasses began to thrive again, they spurred the growth of even more grasses. “Because we have more seagrass, we’re getting more seagrass because it’s improving the quality of the water.”

Although Tampa Bay has achieved its long-awaited seagrass goal, partners in the Nitrogen Management Consortium must keep working to maintain this progress. The region’s population is expected to double by 2050, which will lead to new and increased sources of nitrogen pollution. Emerging challenges like climate change, sea level rise, and ocean acidification could hamper efforts.

“We’ve still got work to do,” said Greening. “But the important thing is that the bay seems to be resilient enough now that it bounces back.”