Study shows Westport River losing salt marshes at an accelerating rate

Salt marsh islands in the West Branch of the Westport River declined by nearly half during the past 80 years, pointing to a troubling trend of loss that is likely affecting coastal habitats throughout Buzzards Bay and along the East Coast, according to a new report by the Coalition, the Buzzards Bay National Estuary Program, the Marine Biological Laboratory Ecosystems Center, the Westport Fishermen’s Association, and the Woods Hole Research Center.

The findings of this study in the Westport River have troubling implications for salt marshes around Buzzards Bay and along the East Coast. (Image: Chris Neill)

By studying aerial imagery of six salt marsh islands in the West Branch of the Westport River, scientists found that the total area of salt marshes consistently declined during the past 80 years, with losses dramatically increasing in the past 15 years. Altogether, the six islands lost a total of 12 acres of salt marsh since 1938. Each island lost between 26 and 66 percent of its marsh area, averaging 48 percent across all six islands.

If marsh losses continue at the accelerated rate observed during the past 15 years, the Westport River’s marsh islands could disappear within 15 to 58 years, according to the report.

“If you do a projection, it’s really discouraging,” said Coalition Science Director Dr. Rachel Jakuba, who coordinated the study. “The salt marsh islands that are currently a characteristic feature of the Westport River could be gone in 50 years.”

Salt marshes are important because they filter out pollution, provide habitat for wildlife, and protect homes from flooding. More than half of commercial fish species on the East Coast use salt marshes for some part of their lives.

The study did not find a single cause of the accelerating loss of salt marshes, but cited nitrogen pollution and sea level rise as two key factors that contribute to marsh loss. Dredging projects, erosion from large storms, and grazing from crabs may also further increase losses.

Nitrogen pollution is increasingly being identified as a cause of salt marsh losses. Long-term data show that the Westport River suffers from too much nitrogen pollution, with the largest source being home septic systems. Although nitrogen pollution fuels the growth of plants, it can also cause the underground root network of salt marshes to become sparse and weak. By examining samples of marsh plants and sediment, scientists found a relatively low ratio of underground roots and rhizomes to above-ground plant parts at all six islands. This low “roots to shoots” ratio suggests that all of the river’s salt marsh islands are affected by nitrogen pollution.

Dr. Linda Deegan, a senior scientist at the Woods Hole Research Center and the Ecosystems Center at the Marine Biological Laboratory, conducted an experiment on nitrogen pollution in salt marshes in the Plum Island estuary in northeastern Massachusetts beginning in 2003. She and her colleagues found that when marsh plants are exposed to high concentrations of nitrogen in the water for a long period of time, they produce fewer roots and decomposition increases, which leads to salt marsh loss. “The low ‘roots to shoots’ ratio finding in the Westport River is very similar to our experimental results in Plum Island,” she said.

As sea level rise accelerates due to climate change, salt marshes are at risk of drowning from the rising waters. Of the six salt marsh islands studied, the island with the lowest elevation lost the greatest number of acres since 1938, whereas the two islands with the highest elevations lost the fewest.

“The lowest elevation islands are the most vulnerable to effects of accelerating sea level rise, but marshes on these islands also receive the most nitrogen from contact with flooding tides,” said Dr. Christopher Neill, senior scientist at the Woods Hole Research Center and former director of the Ecosystems Center at the Marine Biological Laboratory. Neill chairs the Coalition’s science advisory committee and advises the Coalition’s Baywatchers monitoring program, which has been collecting data on nitrogen pollution for the past 25 years from more than 30 harbors, coves, and rivers. “We strongly suspect these multiple stresses likely combine to accelerate marsh disappearance in many places.”

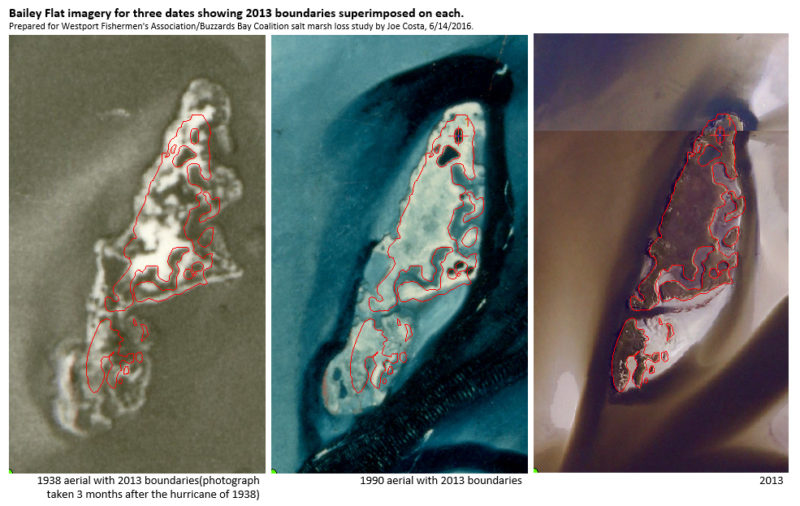

Scientists looked at aerial photographs of the Westport River to “go back in time” and see how the river’s salt marsh islands have changed over time. (Click image to view full version.)

In addition to field work, the study analyzed at least nine aerial images of each salt marsh island from 1938 to 2016. Using specialized mapping software, researchers determined how many acres of marsh existed in each aerial image to measure loss over time.

“We were able to ‘go back in time’ and look at changes over the decades at a level of detail that few people have,” said Dr. Joe Costa, executive director of the Buzzards Bay National Estuary Program. “Over time you can see tide pools forming on top of the marsh and growing, and you can see the boundaries of salt marsh islands receding.”

Salt marsh loss is not unique to the Westport River. Marsh loss has been observed in other rivers, harbors and coves around the Bay and along the entire East Coast. The findings in Westport could be an indicator of the future of salt marshes throughout southeastern Massachusetts and beyond.

“People from communities across the Bay have been coming to us and asking ‘What’s happening to my salt marshes?’” said Coalition President Mark Rasmussen. “Global climate change, exacerbated by nitrogen pollution from local wastewater sources, is having real effects here in our backyard on Buzzards Bay.”

The Westport River salt marsh study partnership between the Coalition, the Buzzards Bay National Estuary Program, and the Marine Biological Laboratory Ecosystems Center formed in 2015 when the Westport Fishermen’s Association first raised concern of rapidly accelerating salt marsh losses with the Coalition.

“I noticed the marshes were not the same as they were back in the 1970s,” said Jack Reynolds, president of the Westport Fishermen’s Association. Back then, Reynolds would use the salt marsh islands as spots to mark his favorite fishing locations on the river. “I thought, ‘There’s something going on here that’s just not right.’”

If salt marsh losses continue at the accelerated rate observed during the past 15 years, the Westport River’s marsh islands could disappear within 15 to 58 years.

Although the effects of climate change are a global problem, there are local solutions that could help improve the health of salt marshes in the Westport River and beyond. One of those solutions is to reduce nitrogen pollution from septic systems and other sources. This will help salt marshes grow stronger, healthier root systems and enhance the stability of the marsh islands.

One critical tool to reduce nitrogen is a Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL): a state-set pollution limit on the amount of nitrogen the river can handle while still maintaining clean water standards. TMDLs are created for waterways like the Westport River when they don’t meet those clean water standards.

We’ve been waiting for the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) to implement a TMDL for nitrogen in the Westport Rivers since 2013, when the agency assured us that the final TMDL would be complete. Last month, MassDEP finally submitted the final Westport River TMDL to the U.S. EPA for approval – but the EPA still has not approved it, even though the Clean Water Act requires them to do so within 30 days of its submittal. We sent a letter to the EPA this week urging them to issue the final Westport River TMDL immediately.

The longer it takes to issue these pollution limits, the worse the problem gets – and the more expensive it will be for communities like Westport to solve it. The Westport River has now been languishing on the state’s “dirty waters” list due to nitrogen pollution for an astonishing 15 years.

Stay tuned by subscribing to our email newsletter (below) or following us on Facebook for the latest updates on the Westport River TMDL and our efforts to reduce nitrogen pollution in all of the Bay’s waterways.